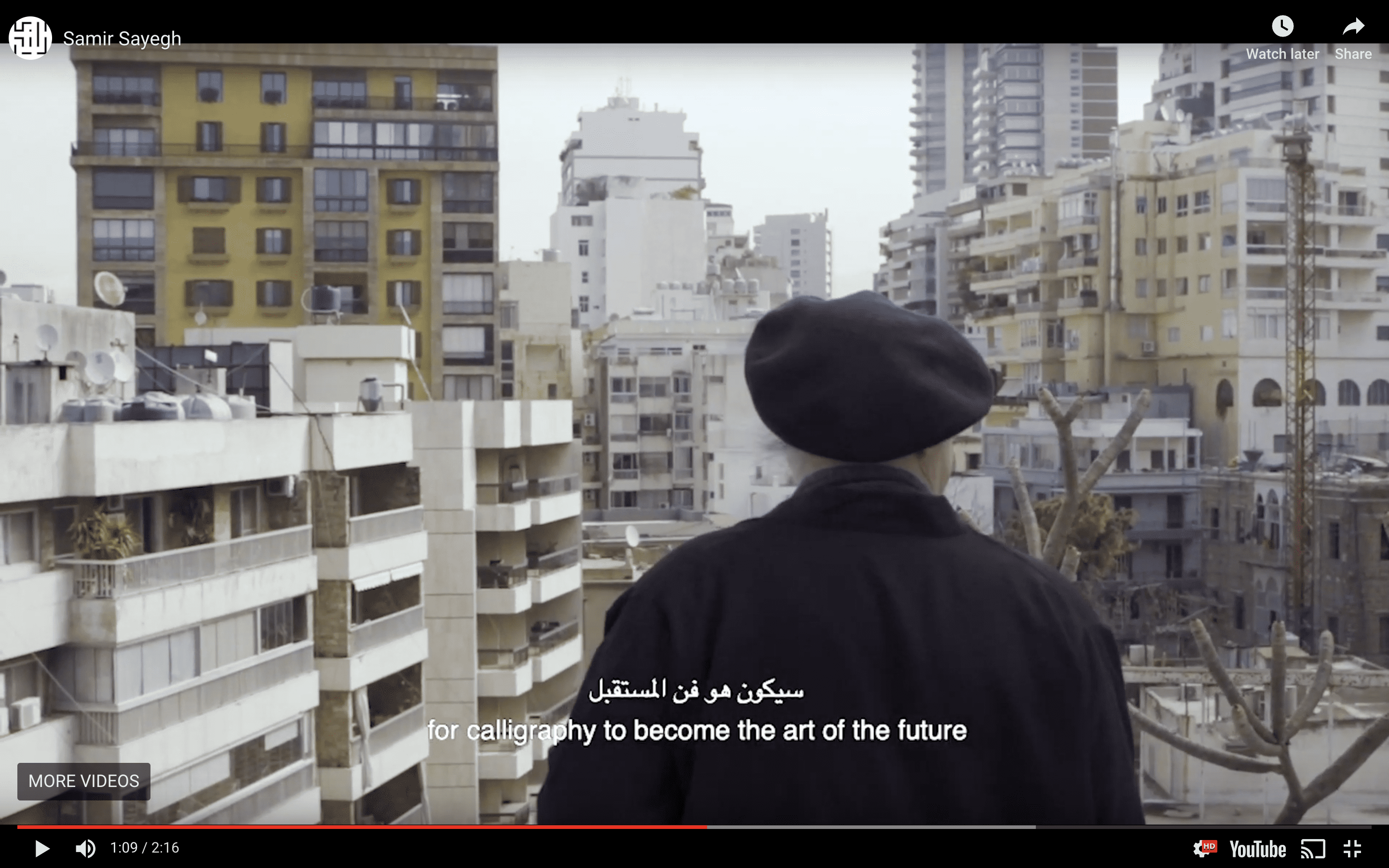

Born in Lebanon, 1945, Samir Sayegh is a pioneer of modernism in the Arab world. An art critic and historian, he wrote about the contemporary art of the Arab world in the Arabic press from 1970 to 1985. His own practice is driven by a deep interest in the formal power of letters and he was one of the first who sought to liberate calligraphy from language and meaning in an effort to create a universal visual language.

As such, he is considered as one of the most avant-garde Arab master calligraphers. Also a prolific writer, Sayegh has published numerous articles and essays on art and aesthetics as well as being the author of several books, two on Sufi poetry and one on Islamic art. From 2003-2007, he was a lecturer in the Architecture and Graphic Design department at the American University of Beirut.

Sayegh lives and works in Beirut and is represented by Agial Art Gallery (Beirut). Art Dubai interviewed and filmed him in his Beirut studio:

Q: You talk about the relationship between writing and calligraphy being at times, perfection and at other times, a struggle. For you, in your art work, do you aim to find a balance between the meaning and the content?

(Sayegh) From the beginning, I sought to liberate calligraphy from language, such that it won’t only be a tool to carry the meaning of words and does not become just a craft. I sought to make calligraphy come out of the circle of balance between usefulness and beauty to entirely take the side of beauty and become beauty for beauty itself.

As for writing, I felt that during the civil war in Lebanon and after the series of defeats in the Arab world, that language in poetry had become an ineffective mode of expression, and so I stopped writing poetry. The reconciliation came when I started writing about letters, when letters started writing their memoirs and correspondences, and make dialogues between each other, that is, when language became form for calligraphy and when calligraphy become content.

Still, language remains for me the medium that joins earth and heaven and unites existence and the unseen, and calligraphy remains in its first manifestations a form for the word of revelation.

Q: How do you choose the texts for your calligraphy compositions?

The title of my first exhibit was “what cannot be written and cannot be said” and it was without any texts. In following exhibitions, the text was limited to one word: “Allah” under the title “The multiple One”, or other words such as “baraka” (blessing), “ne’ma” (grace), “suroor” (delight), “hob” (love), “hurryah” (freedom) and “salam” (peace).

Then the text became one letter, and later texts without name or pronunciation, and writing became signs without letters.

Samir Sayegh talks to Art Dubai

Q: Calligraphy is full of strict rules regarding dimensions of the letters and proportions. Is it important for you to stick to these in your work?

Since my first steps in calligraphy, I had to quickly override the issue of rules and rhymes that were established by Ibn Muqla, then asserted by calligraphers in the times of the Ottoman sultanate. My contemplations on the early Kufic scripts led me to the inference that rules and rhymes are not fixed, but moving, multiple and variable. They are based on dialogue and interaction between their elements, but more importantly they do not precede creativity nor planning but rather come with them and after them, as a result. And creativity is not one but multiple.

In poetry, I quickly went past the rhymes and verses of Al Farahidi (an ancient Iraqi poet and lexicographer), to listen to poems in prose form and appreciate the music of language in its flow, with the realisation that they would align with ideas, feelings and beats of the heart.

Q: How then, do you find your own unique aesthetics?

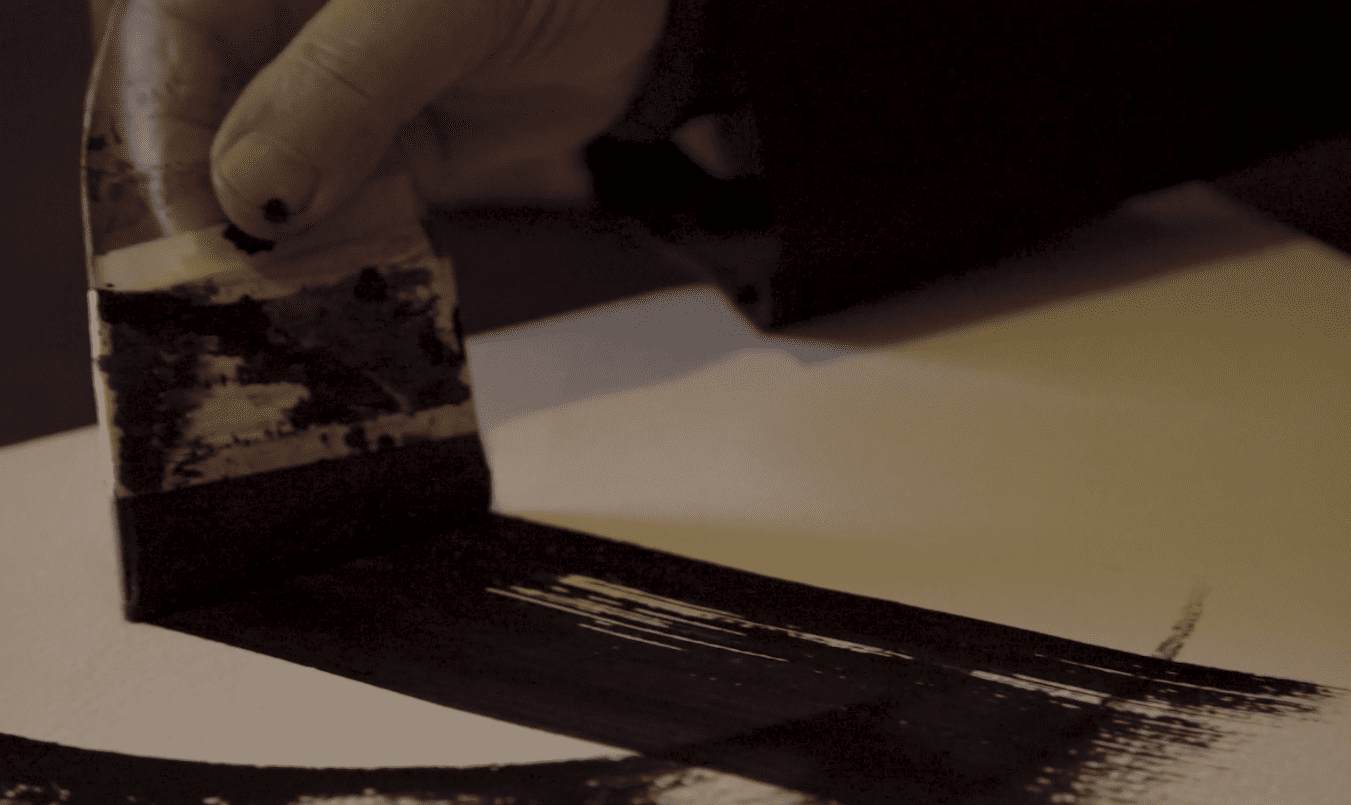

Aesthetics are embodied in the elements that compose the form, as well as in the nature of colours and inks. They are in the movement of forms, in their interaction and communication, association and fusion. They reside in the dialogue between tall and short, straight and curved, and in the transformation from thickness to transparency and from warmth to coldness.

They are also in the safe and successful exit from the inner self to appear and become manifest on the pages of a work of art. They lie in the sincerity and truthfulness of carrying what was being felt deep in the soul and the spirit.

Samir Sayegh in his studio in Beirut

Q: Is it important for you to give your work a contemporary look and feel? Why?

Of course, I strive to give my work a contemporary style and presence, but this endeavour is always equivocal and ambiguous. I sought inspiration from the past to get to the future, and called this body of work “the return to the future”, as though time were circular, and while we progress towards the end, we move towards the beginning.

This ambiguity comes from the fact that contemporary time is either the end of the past or the beginning of the future. But I believe in the unity of being and also in the unity of human beings. The one who goes into this unity and merges with it, leaves the phases of time and the frontiers of place, to be always contemporary.

Q: How do you express your inner thoughts and feelings through the work you do?

The term “express” does not apply to the art of calligraphy or to the arts that are based on form. This does not mean that the artist here does not have feelings or emotions. Here, feelings, emotions, thoughts, imagination, will and intuition all combine on the inside to become the energy that thrusts towards the hand, eye or imagination to convert into forms on the pages of the art work.

The lines and shapes are thus originally feelings, emotions, thoughts and visions and the viewing eye can also read these.

Q: How do you hope that a viewer feels when encountering your work?

What I hope viewers will experience is to know how to see not what to see, because the secret of the work of art is in their hands, and thus it is they who determine its content.

If they can, through contemplation and reading of these forms, go through them and reach the point where they come from, that is to the inner side of the artist, they would be able to encounter the energy that produced the work of art and feel its elements, attributes and particular mood.

They would be meeting with the essence of the soul, or the essence of similar human experiences. Thus, the viewers’ reading turns into a creative process equal to the artist’s own creativity.

Q: What do you think needs to be done in the Arab region to propel Arabic calligraphy further as an art form?

While we have to assert our view that the art of Arabic calligraphy is a supreme, ancient and original art, we should wait for it to come from the front not from the back; from our future not our past. We have to stop learning its rules and rituals, refrain from exercising its principles and styles, because this freezes it and keeps it within the limits of a craft.

We also have to view it as the art of the form, par excellence, and as an art capable through this form to translate visions, suggestions, feelings and thoughts into forms that turn again into a new language.

We have to free it from its functions and uses and all responsibilities, so that it returns to being an art form by itself.