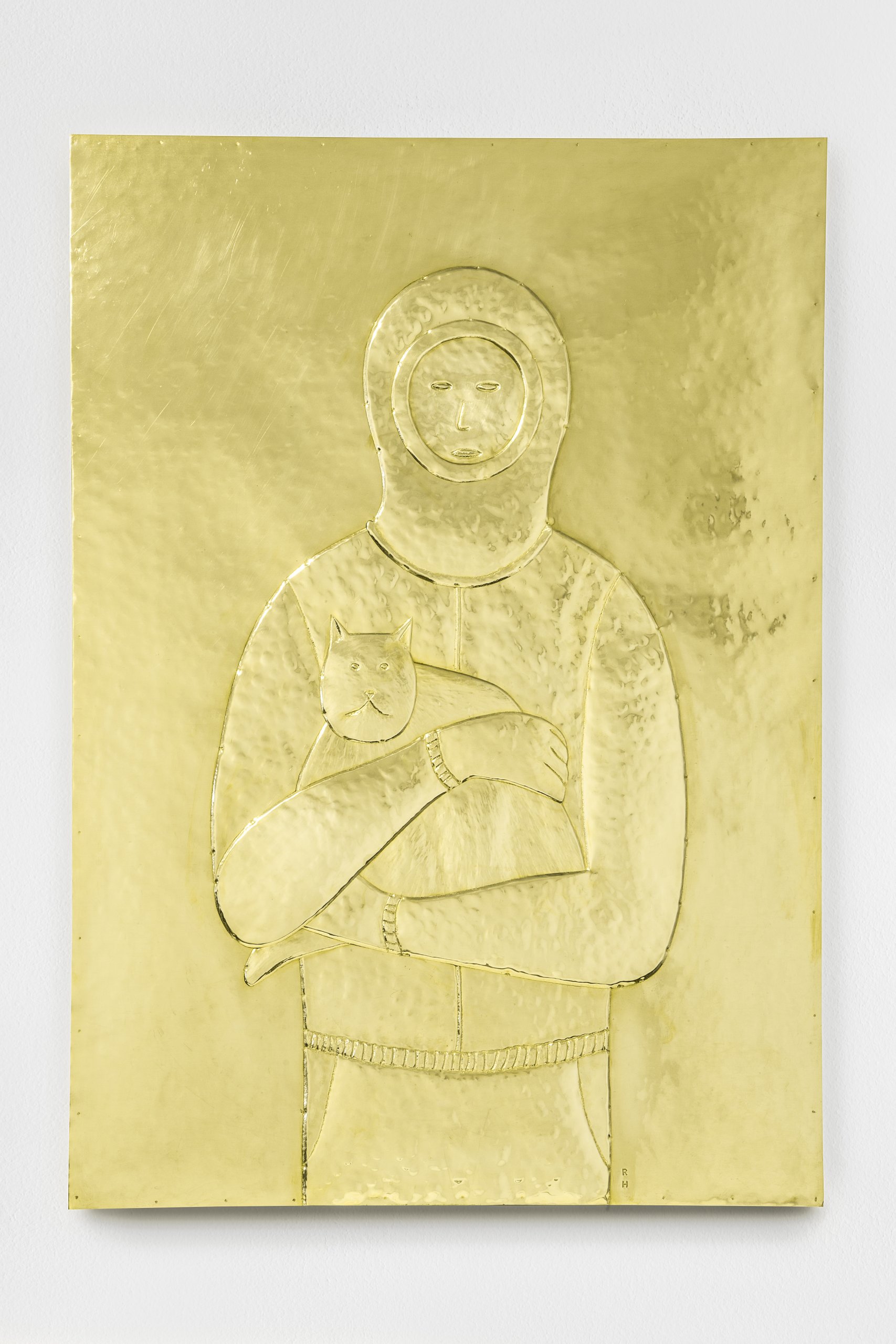

An astronaut cradles a cat in his arms. For reasons I cannot immediately identify, I am drawn to this image by the Mexican artist Rodrigo Hernandez. Is it the golden shimmer emanating from the hand-hammered brass sheet? Or the pared-down figures in this nocturne, guileless icons of a once-and-future belief in compassion? The heroic figure, although costumed for an interstellar voyage, is portrayed in a tender domestic gesture. As we grapple with the deadly Covid virus, isolated from one another, our hearts crave such simple yet redeeming acts of care and healing.

Half a century ago, a cat named Félicette was unfelicitously launched into space with electrodes implanted in her body to study the effects of space flight on living beings. She is the first and only cat to have been launched successfully into space (ironically, from Hammaguir, a launch site in the former French colony of Algeria, in 1963). A few months after Félicette experienced her five minutes of weightlessness, her brain was cut open by scientists, in the cause of research.

In the Covid era, we are no different from this cat who was locked into a capsule and hurled into zero-gravity space. Shut in, disoriented, we have been helpless, fearful of our lives. Except that, while the cat was a victim of humankind’s Cold War politics, we are the victims of our own devastation of the planet. Perhaps art and poetry can show us a way forward, connecting us to one another across the Global North/ Global South, but also the human/non-human, animate/inanimate divides?

This year’s Bawwaba (meaning ‘gateway’ in Arabic) features artists from Peru, India, Pakistan, Mexico, Nigeria, Angola and Chile. It is an invitation to slow down, to concentrate on facture or the act of making; on techne as a form of resistance against the forces of authoritarianism. By techne, I mean a haptic investment of the self in making and unmaking things, rather than a rhetorical affiliation of the self to cold, alienating conceptualisms.

The paintings of the Nigerian artist Tonia Nneji and the Pakistani painter Wardha Shabbir, as well as the Indian printmaker Soghra Khurasani’s woodcuts, are informed by their critical, gendered subjectivities. Sensorially rich, these works signal diverse histories of belonging and exclusion. The textile patterns in Nneji’s paintings affirm her Igbo and African affiliations while critiquing religious orthodoxy. Shabbir’s repurposing of the miniature painting tradition mediates between her South Asian heritage and contemporary political urgencies. Khurasani’s fictive landscapes of epic disquiets, gouged and scratched into the surface of her prints, articulate the rage and vulnerability of the Indian Muslim woman in a country dominated by an aggressive Hindu majoritarianism.

The Peruvian artist José Luis Martinat’s stark works, made with traditional embroiderers from the Grados family, hang like fraying banners or false promises. The Grados family has for decades embroidered insignia for the president on the finest material imported from Europe. By contrast, Martinat’s works are made from distressed industrial materials and inscribed with signs questioning the Enlightenment idea of ‘progress’.

While Martinat politicises the language of abstraction, the Chilean-American artist Ernesto Burgos and the Indian artist Mona Rai create expressive works brimming with emotional intensity. Burgos reshapes an everyday material like cardboard by crumbling or folding it. Then freezes it in fibreglass and paints over it in a vivid abstract expressionist register. Rai, a maximalist, revels in a multiplicity of materials and moods – quotidian and cosmic. Her dazzling surfaces are covered with glitter, brocade and foil or burnt with electric rods and pricked with a needle. They could shimmer with intimacy or shower us with a rain of grace.

The Indian artist Vipeksha Gupta’s minimalist works on paper are composed of layers of charcoal and graphite punctuated by mysterious folds. Spirit guides, they encourage us to make friends with the other half of ourselves, which we hide or cannot reconcile ourselves to.

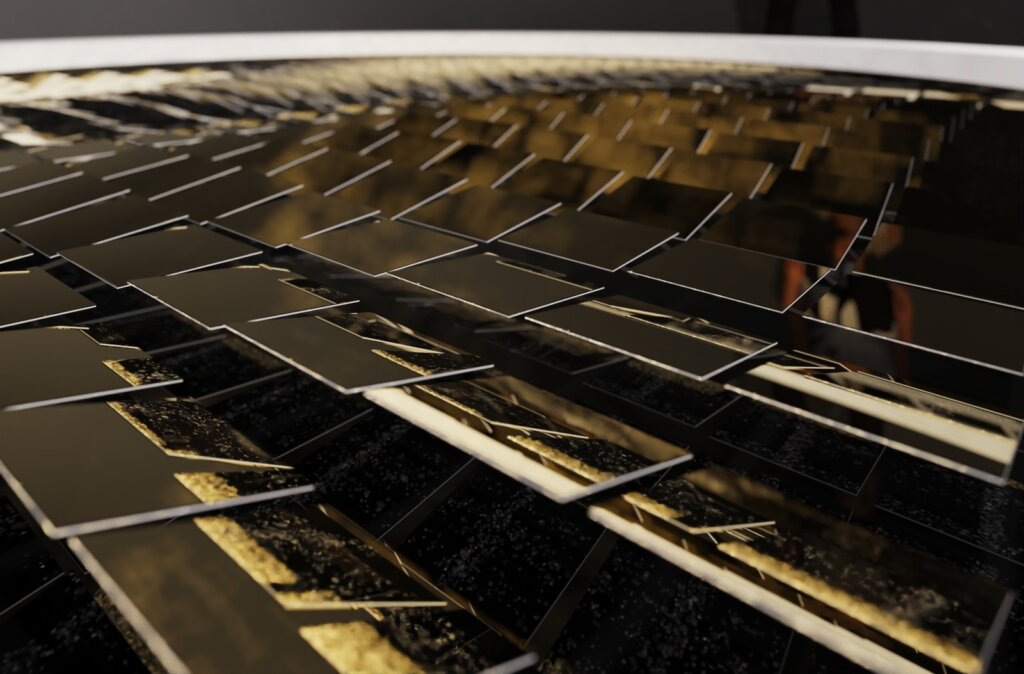

In the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda’s monochromatic photographs, spectral structures come up like mirages in a desert. They caution us against the violence unleashed by hyper-urbanisation against the environment – a process familiar to the artist from his hometown in Angola, it resonates for Dubai.

The Indian artist Ranbir Kaleka’s fabulous video installation is a pilgrimage through landscapes of desolation in which – accompanied by a sound track rich with volcanic seething, hooting trains and plangent elegies – we glimpse multiple catastrophes. Kaleka suggests that we are as vulnerable as the species we have hunted into extinction, and our haunted pasts prefigure our threatened futures.