‘Rewind’ is a feature series on the Art Dubai blog, looking at the life and personality of a Modern artist from the Middle East, Africa or South Asia, who is connected to the fair through one of the Art Dubai Modern participating galleries. The stories are told through the eyes of a close relative, and are written by Myrna Ayad.

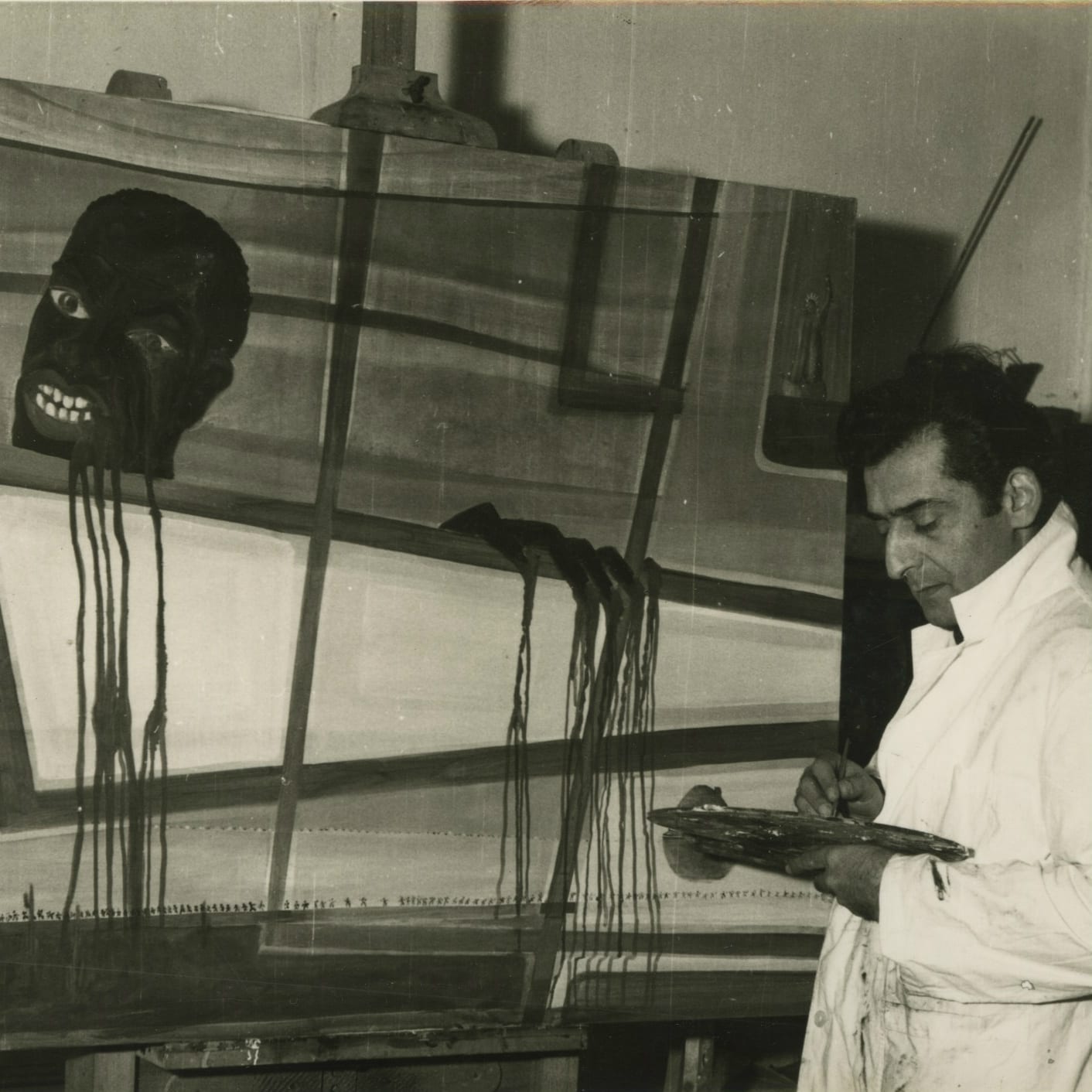

Aref & Hala at Gallery Epreuve d’Artist. Courtesy the Aref El Rayess Estate.

The story goes that instead of helping his father with the financial management of the family fruit and nut import and export business in Senegal, my father would escape to spend time with the local tribesmen and was fascinated by their lifestyle and colours. I think his big break was this African period of watercolours; those are the works that led to his discovery as an artist after all: a journalist was interviewing Druze women, including my grandmother and was blown away by his paintings. My grandmother was my father’s biggest supporter and took pride in telling the reporter that these were by her son. The journalist returned, accompanied by reps from the UNESCO and the American University of Beirut (AUB), which led to my father’s first shows at both institutions in 1948.

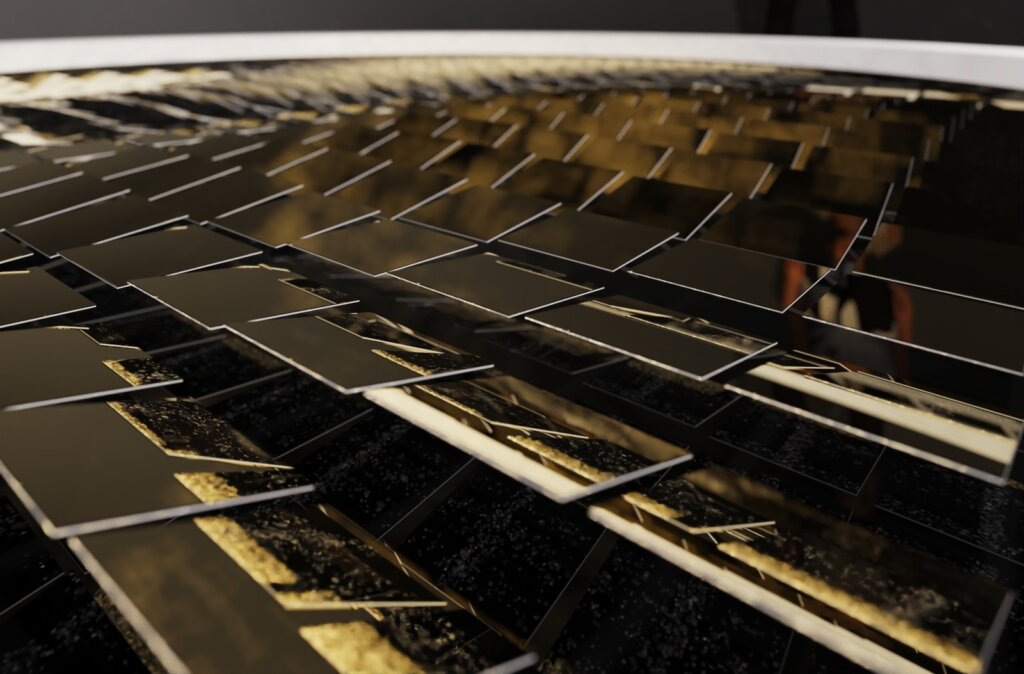

Cells and Organisms. 1966. Oil on canvas, 59 x 74cm. Image Courtesy of The Park Gallery.

I was born in Beirut in 1979, but because of the war, we moved to Jeddah in the early 1980s. Those days weren’t great. Dad painted most of the time and was barely home, working long hours under the sun and he eventually got sunstroke. He would take me for little drives around town. He was always exhausted and would nap in the afternoon. He had a studio at home and I remember paint all over the house. He was very messy; all he cared about was creating art. He would give me little canvases and allow me to explore on my own. I later found that he had saved those paintings. I still remember the smells in his studio and his desert series as it was being created.

Dad was promoted to counsellor in the Jeddah beautification project and worked closely with the then-mayor Dr Mohamed Said Farsi. In Jeddah, he was happy being with his wife and child. Now though, as I am working on his legacy, I believe he was very lonely and that’s where the desert came from, because it represents a lonely place: that’s my instinct speaking. Things got bad with my parents, which eventually led to (an amicable) divorce. My mother got full custody of me and in 1987, she and I moved to Venezuela, where her family is based. Dad moved to Paris and they came to an arrangement where I would spend my holidays with him. In Venezuela, I missed him all the time. I missed his hugs.

Dad gave me freedom and brought out the best in me – he did this with everyone. He was a prolific artist, who would get into ‘phases’; a tunnel of sorts I’d say, and he wouldn’t come out until he was satisfied. He was a caring, giving, loving, affectionate human being, very strong, but also very sensitive. He didn’t care what people thought or said. He was very forgiving, but would never forget. He was practical and got on with making things happen. He was very spiritual and appreciated all religions. In Jeddah, he explored

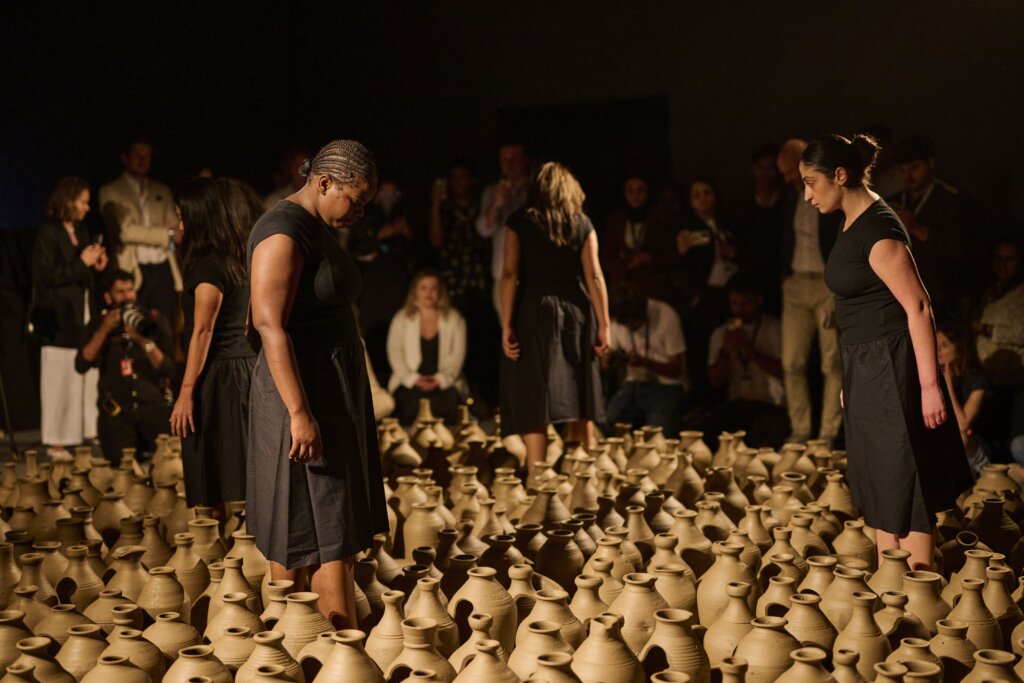

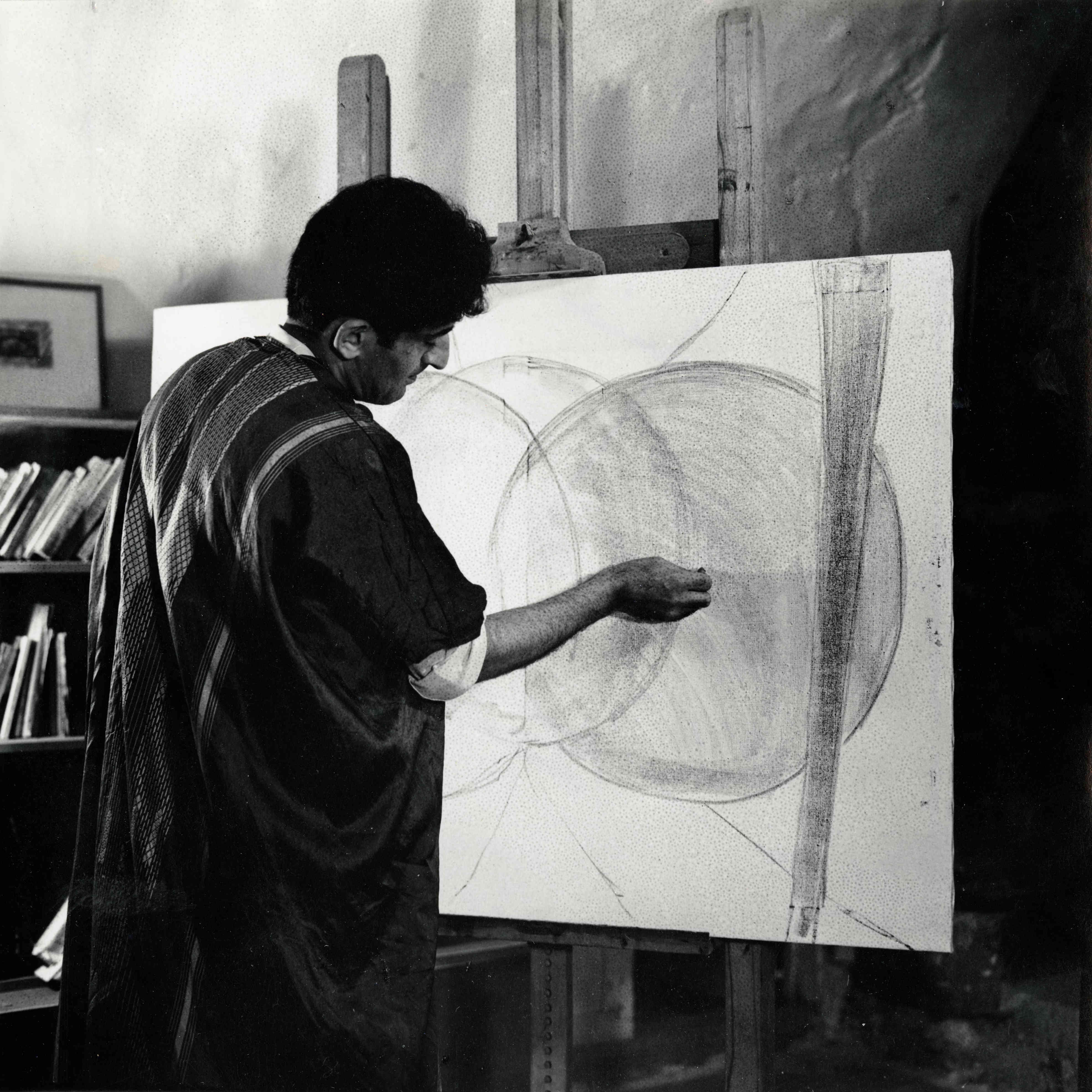

Year unknown. Courtesy the Aref El Rayess Estate.

Year unknown. Courtesy the Aref El Rayess Estate.

Islam. In London, he learnt about Buddhism. In Lebanon he delved into Christianity when he attended the notable St. Joseph School in Aintoura. He was chaotically organised and I understood his artistry only after he passed. All the archives and works tell me this person knew what he was doing from the beginning, and that he had a purpose.

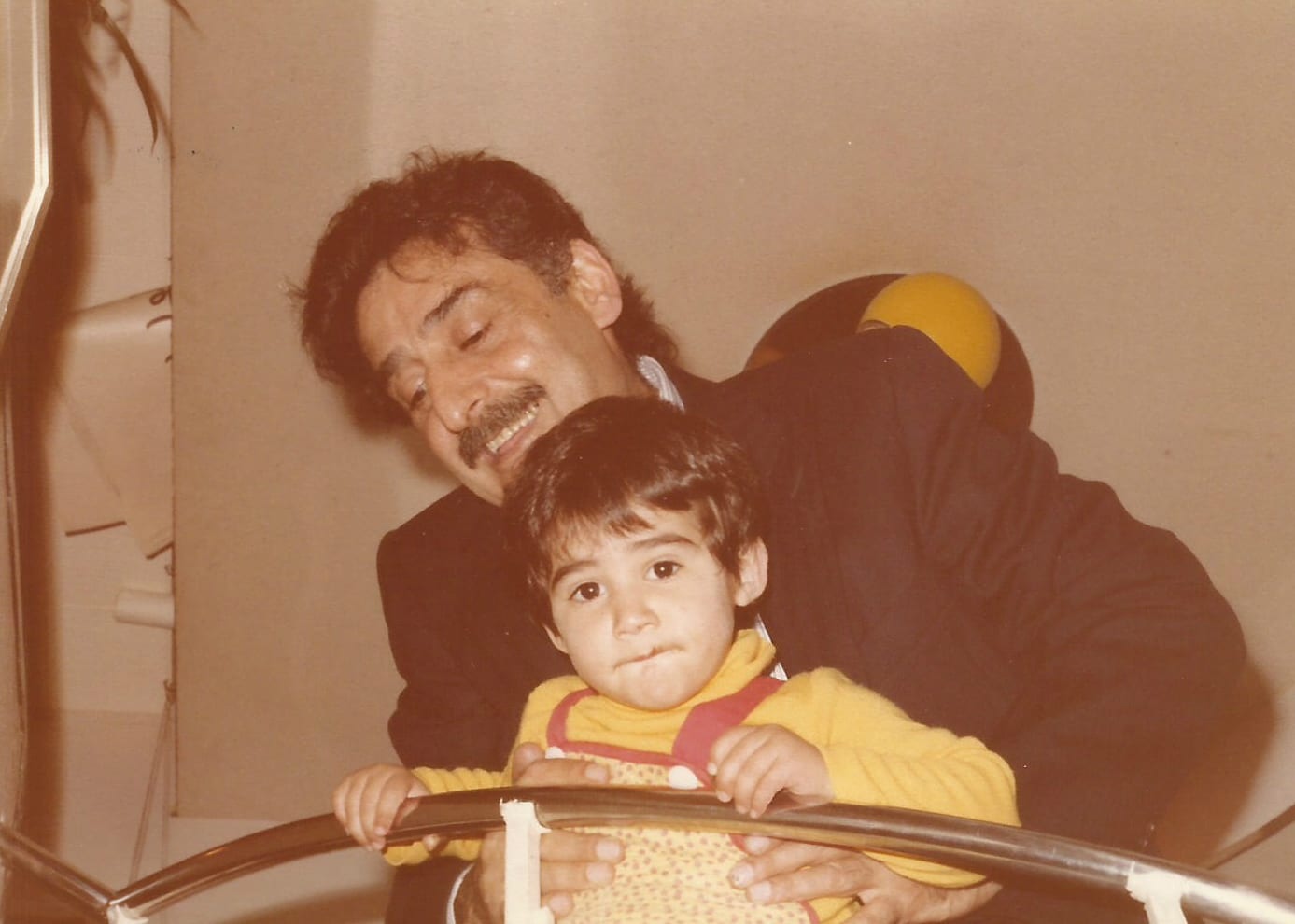

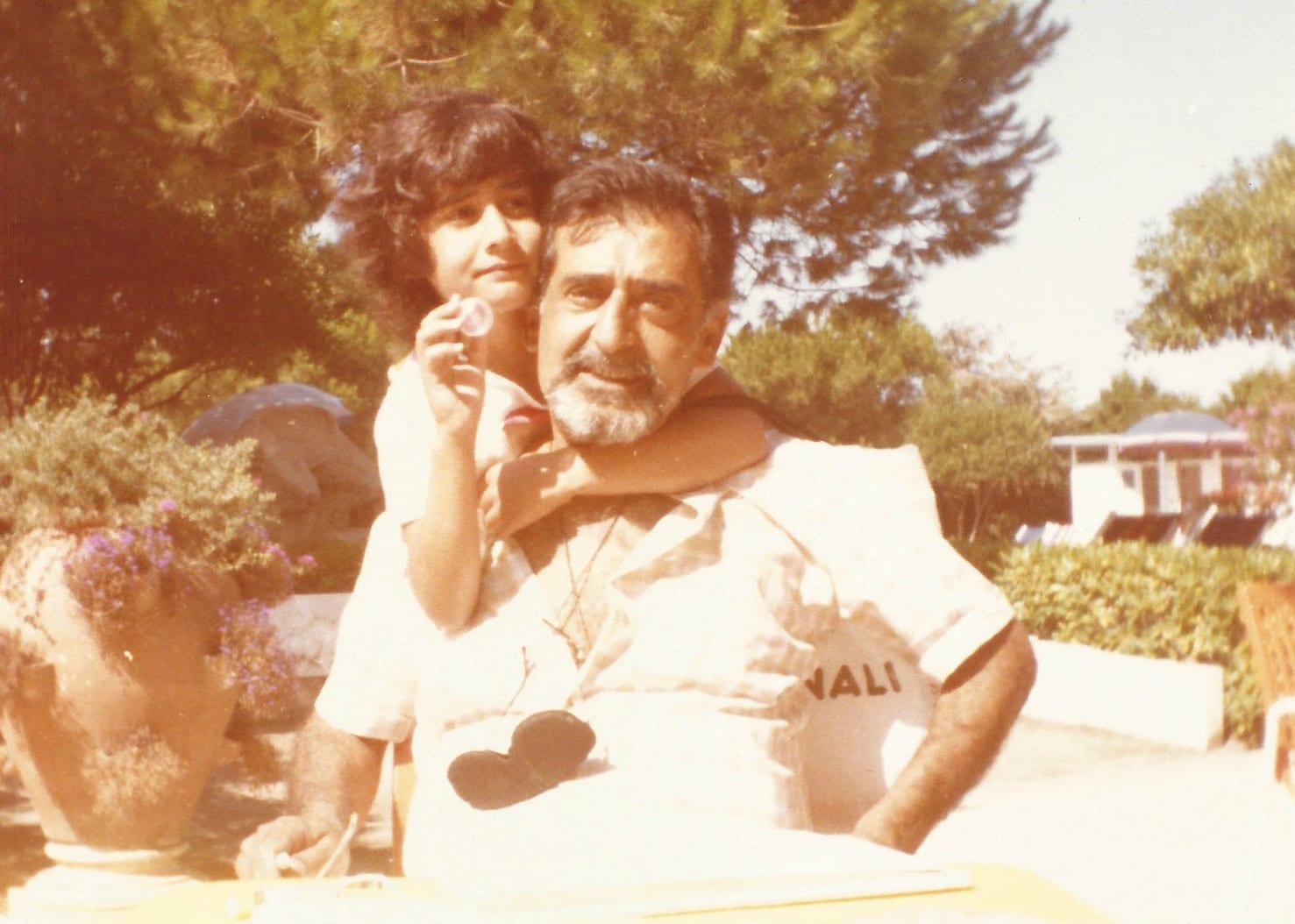

Hala and Aref in Paris, 1989. Courtesy the Aref El Rayess Estate.

In the summer of 1992, while I was visiting him in London, he asked me if I’d like to visit my country, adding, “You are Lebanese.” It was safe to visit and so I did, and fell in love. I celebrated my 13th birthday in Lebanon and said I wanted to stay there with him forever. It was the happiest day of his life; I can still remember how his face lit up. I ended up staying and living in Aley and it was the best decision I ever made. I thank God for that because I had the chance to spent the last years of Dad’s life with him. His work became more abstract. His collages were an escape, a break, a way to bring back creativity in a different way.

In 1996, the Israelis bombed Qana in the South of Lebanon; Mom panicked and decided it would be safer for me to attend boarding school in the UK. In December 1999, I returned to Aley, and my grandfather began interfering in my personal life. After being alone in the UK for four years, this caused issues. My father invited me for a coffee; we chatted and he then took my hand, looked into my eyes and handed me keys to his apartment in Beirut. This is where the Aref El Rayess Foundation is now registered, temporarily.

Dad was taking care of my grandfather while creating works non-stop. I would see his shows at Galerie Janine Rubeiz, the French Cultural Centre, the UNESCO and a few other spaces here and there. There were many works that were dedicated to me. He would encourage me to paint and I actually held two shows. He saw that I had great potential, but instead I rebelled. I was miserable and felt I had no purpose, direction or ambition.

Untitled. 1996. 125 x 125cm.

He would visit me in Beirut, we’d see shows, have a meal together and play backgammon. I would spend time with him and his artsy friends, like Emily Nasrallah, Amal Traboulsi, Cesar Nammour, Joe Tarrab, all these giants, and I didn’t know who they were at the time! I was always surrounded by these intellectuals; I didn’t really understand their language and as a child, I would get bored. I guess I was jealous of his art and wanted more of his attention. I think I pushed him away, but he never went away. In the last two years of his life, I don’t know why but I was distant. I believe that the distance made it a lot easier for me to handle his passing. He was always open and understanding enough to know when I needed my space and allowed it. I’ve always loved him more than anything.

On January 27 2005, he came to visit me with a family friend. They knocked on the door, but I was fast asleep. When I woke up, I called him and someone else answered and told me he was being rushed to the ER. I met him there and found him screaming with pain. He grabbed my T-shirt, pulled me close and said: “Hala they’re going to eat you alive. Promise me you’ll be strong, find a good man who loves, respects and admires you the same way I do.” He knew his time was up. I think everyone knows when their time is up. It took me a long time to come to terms with it.

I stayed in Beirut, where I was introduced to writers and intellectuals, all of whom encouraged me to do something about my father’s legacy. I didn’t know what I was doing at first, and jumped from one idea to another. I learnt about monographs, curators, archiving and things started to roll. The Aref El Rayess Foundation was officially registered in March 2015. We’re still digitising objects in his atelier, from correspondence in several languages, poetry, unpublished writings, to photos, sketchbooks, paintings and sculptures. I am aware that there are around 10-15% more works out there that I don’t have information on. The Aref El Rayess Estate is based in Aley, in the family house where he was raised, and where his atelier is located.

Aref & Hala. Courtesy the Aref El Rayess Estate.