‘Rewind’ is a new feature series on the Art Dubai blog, looking at the life and personality of a Modern artist from the Middle East, Africa or South Asia, who is connected to the fair through one of the Art Dubai Modern participating galleries. The stories are told through the eyes of a close relative, and are written by Myrna Ayad.

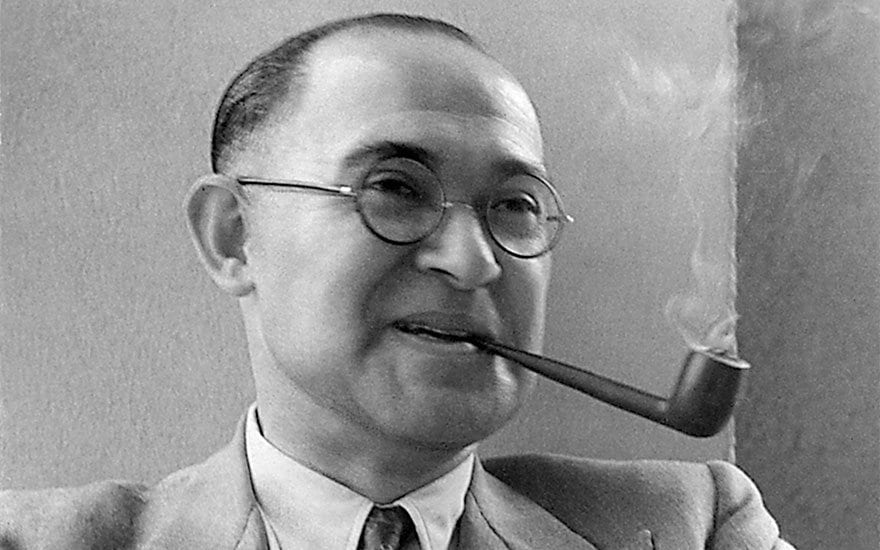

The story on Mahmoud Said’s life is recounted by his great, great nephew, Hashem Montasser.

An aristocrat and judge by training, Mahmoud Said is widely recognised as a pioneer of Modern Arab art. Painting was a passion that began in 1919, when Said was 22 and travelled around Europe, studying at the famed Académie Julian. He left his legal career at 50 and focused on painting for the remainder of his life in Alexandria.

In his 45-year artistic career, Said represented Egypt at the Venice Biennale thrice and participated at the International Exhibition in Paris. Like most modernists from the Arab world, great recognition came later: three of Said’s works sold at auction for millions of dollars since 2010, and most recently, a major catalogue raisonné has been published and launched at Art Dubai 2017. Here, Hashem Montasser, a collector, descendant of Said’s and Art Salon member, discusses life with the great master’s paintings and how Said’s work evokes a bygone era in Egypt.

Mahmoud Said. Courtesy Mathaf Encyclopedia.

“Growing up, I think we all formed an impression of someone called Mahmoud Said that we understood was important. As a child, I knew that he was gifted. My introduction to him came through my maternal grandmother, Ehsan Sirry, whom I was very close to and spent a lot of time with. She was Said’s niece and also first cousin to Queen Farida, King Farouk’s first wife (Said was uncle to both).

Growing up in Cairo, we’d lunch at my grandmother’s home every Friday, and in her dining room was a beautiful painting of fishermen by Said. In the salon hung a big landscape of Aswan. I have a visual memory of where each work hung in her home and in our family home. He’d painted two portraits of my grandmother; one, when she was in her mid-thirties and another, a very special one, when she was about 13 or 14. It hung in her living room, and as she got older, she would spend more and more time there, always with that portrait around her.

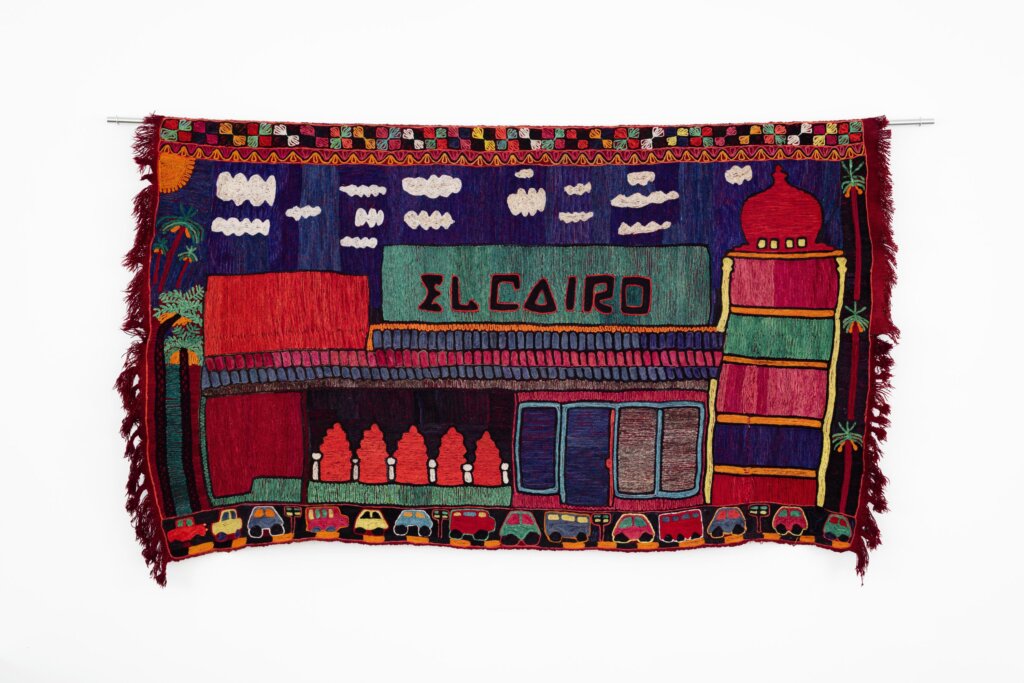

In our house hung smaller works that are now in my home in Dubai. They give a different impression altogether – one of a versatile artist. Said had studied in Paris and travelled around Europe, and some of those smaller works were live paintings done in the 1930s. The images include Venice, Aswan, a minaret and a nightclub, where the light shines on people dancing. That one is a favourite, because it’s somewhat conceptual.

Portrait de Madame Batanouni Bey, 1923. Image Courtesy Sotheby’s.

My grandmother told me his story – that he was a good lawyer, more or less pressured by his father to remain in law, although he was clearly becoming a successful painter. Said practiced law until his father passed away, which makes me believe that he did so just to please him. He then resigned as a judge and became a full-time painter. The Alexandria of his time was extremely cosmopolitan and a lot of his paintings sold to Greeks and Italians, which meant that his work went around the world.

We always had the impression of him as someone very kind – I’m not sure if that’s because of how he looked or what my grandmother said, perhaps both. He painted portraits of a lot of family members and gifted them these paintings; some, they purchased at nominal prices.

Beyond being a relative, his art always struck me as particular and very different from other artists of his era. I found his style worldly and I think that when he covered topics like the Nile and villagers, he did it with a singular touch. It felt somewhat sophisticated, a lot more cosmopolitan, really focused on beauty and far less nationalistic compared to the work of Abdel Hadi El Gazzar, for example.

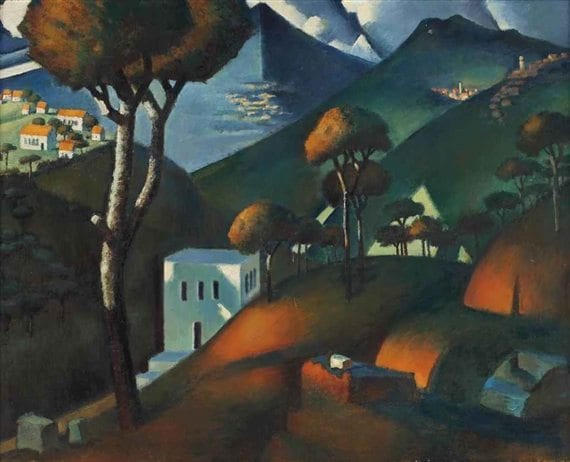

Apres la Pluie au Liban, 1954. Image Courtesy Christie’s.

By the time I was in my teens, I had developed a sincere interest in Said, to a large extent because there was a relation. But, also, my interest in Egyptian modernism piqued as I had begun attending art exhibitions with my mother, who had picked up pieces over the years – pieces that I grew up with and which stayed with me. In my early twenties, I bought my first work: a sculpture by Adam Henein and I continued to acquire thereafter.

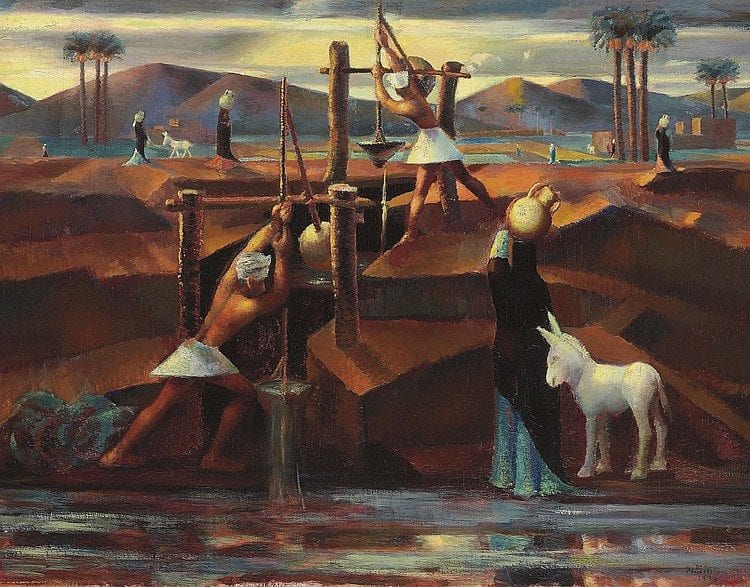

In 2010, Said’s Les Chadoufs (1934) sold for a record of over $2.4 million at Christie’s in Dubai. My mother was still alive and I told her about it; she was more interested in what works people liked and were buying. For me, it was more of a feeling where you feel justified in your view that this was a very important artist. I do believe though, that these are Middle Eastern prices, and that if his works (as well as those of some others) were placed in a global context, they would be more expensive.

Les Chadoufs, 1934. Image Courtesy Christie’s.

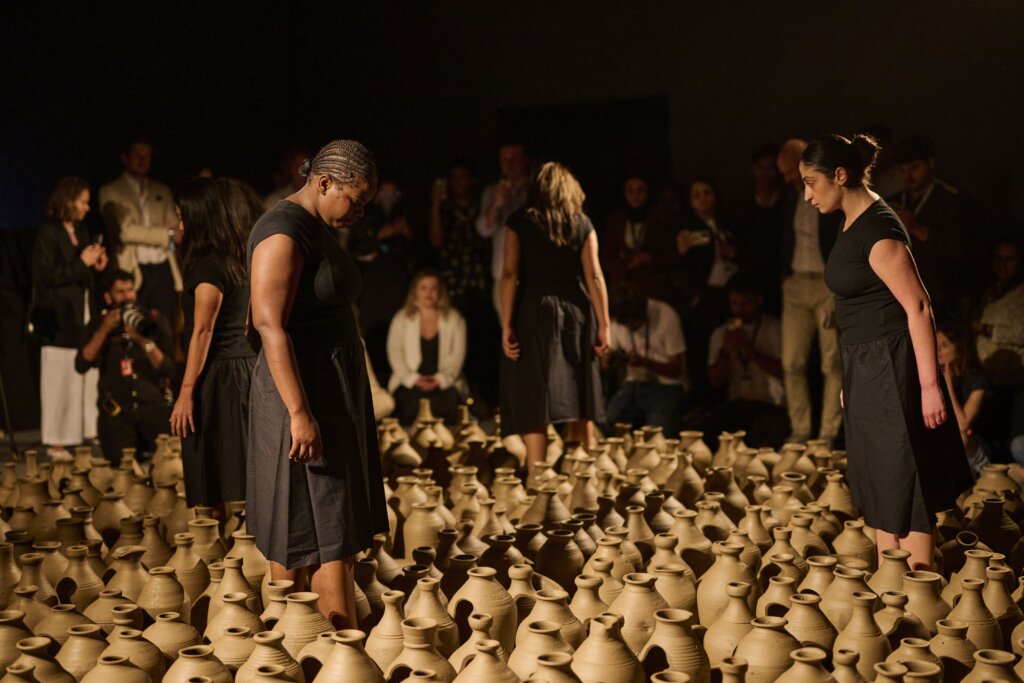

Said’s catalogue raisonné has just been released and that was very gratifying and we supported it gladly. The high-quality work that Valerie Hess and Dr Hussam Rashwan have done is not only great for enthusiasts and art students, but that whole era is very important to access. I hope the tome is a catalyst for others to do the same thing.

Today, I look at the little paintings in my home and my kids see them too and know who Said is. I’ve been with these works all my life and I like this thread of continuity: they remind me of home, and that’s important.”

The Whirling Dervishes, 1929. Image Courtesy Christie’s.