Mumbai, formerly referred to as Bombay, and now lovingly known as India’s “City of Dreams,” boasts a long, complex, and rich history of entertainment and culture. Both an economic centre and a cultural capital, Mumbai is a city characterised by dynamism and inspiration, earning its reputation as the “Maximum City.” The city’s bustle and allure has attracted thousands of migrants, Bollywood-hopefuls, and artists. Once seven islands ruled by different indigenous groups, Mumbai came under Portuguese colonial rule in the 1500s, who eventually ceded power to the British in the late 1600s. During British rule, the city was merged into a singular landmass, and became a prominent site for cotton production. Also an established trading hub, Mumbai’s position as a port-city, alongside its intricate history, has since transformed it into a prosperous space for change, innovation, and creation.

A hub of industry, creativity, and opportunity, Mumbai is often described as a microcosm of India: dense and fast-paced, chaotic and vibrant, deeply rooted in history yet forward-looking. The city’s cultural landscape mirrors this dynamism. From British-era museums to new cutting-edge contemporary galleries and grassroots initiatives led by artists and local communities, the arts scene has seen a gradual evolution. The high population density and literal space constraints – inherent to Mumbai – has influenced how these cultural spaces are shaped, sustained and utilised.

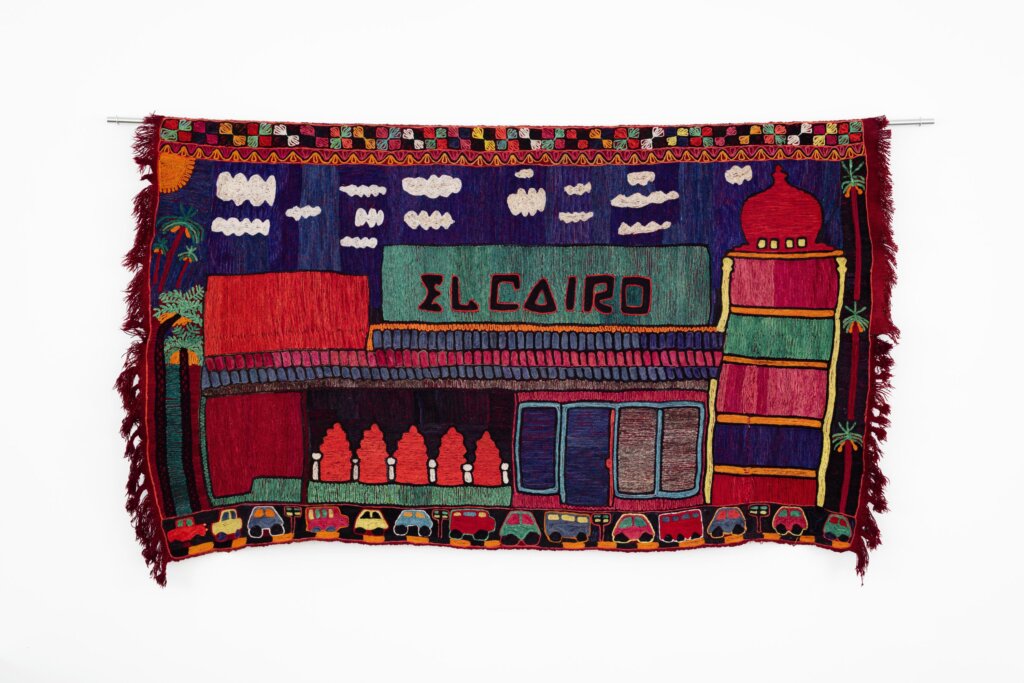

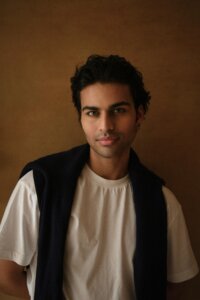

Image courtesy of Sahil Behal

Mumbai-resident Akshat Rajan, a leading experience designer, collector and founder of Akiko Rhythm, guides us through the many cultural spaces – and the ingenious innovation and collaboration that marks their essence.

“Mumbai is beyond emerging, Mumbai has already arrived,” announces Akshat Rajan, a creative thinker, art collector, and space designer who grew up in the city. “The city, of course, has a long history, but living in the contemporary moment is something else.” As an experiential designer, he cannot help but look at the city as a space itself. “What composes a space in the landscape of Mumbai is changing,” he says, adding, “Mumbai is one of the most densely populated cities in the world. I find it fascinating to study the lack of physical space –– specifically free, public, open spaces –– and how this influences how people occupy the city,” shares Rajan

For Rajan, culture is a space for community. During the British era, what constituted a space was reflected in museums like Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) and the Bhau Daji Lad Museum, both of which were set up with the ambition of Britain to highlight its colony’s crafts. After Independence in 1947, new institutions such as National Gallery of Modern Art and Jehangir Nicholson Art Gallery (JNAF) came into being, providing the public a space to engage and participate in shaping cultural and social life. Legacy gallery Chemould Prescott Road – now celebrating its 61st anniversary – found space within JNAF in 1963, and since then, prompted the gradual emergence of an art scene in the Kala Ghoda District – the main cultural district in South Mumbai.

Within and outside traditional institutions, Mumbai has always and continues to carry an independent spirit, shaped by progressive, socially-led ethos. “Mumbai is home to the iconic Gateway of India, which Gammon India built 100 years ago… In many ways, the city has been the Gateway to India since then,” Rajan says, explaining how Mumbai’s art scene reflects its diverse and multicultural environment. As the financial capital and centre for Bollywood films to art, design, fashion, business and entrepreneurship, the city has been a space where culture, commerce, and creativity continually converged.

Today, the city is witnessing drastic change. With an influx of people and high-levels of construction marking its landscape, its residents are forced to reimagine how they live, create, and participate in society. This emergence of “liminal spaces,” as Rajan describes, is marked by a more inclusive and collaborative nature, in which industries are merging and creating interdisciplinary experiences. In short, “no space can be and do just one thing.”

“Mumbai is beyond emerging, Mumbai has already arrived,”

When asked what space means to him, Rajan immediately responds: “Safety.” It may mean the opportunity to be present, to feel a sense-of-self, to explore, or to feel free of judgement. He roughly categorises these spaces into four: institutional spaces, social spaces, public spaces, and temporary spaces. Although they exist as self-sufficient, independent categories, they often fall into each other and collide. With a passion for spaces that champion intentionality, collaboration, and community, Rajan delves into a variety of places that have distinctly shaped Mumbai’s art scene and what distinguishes the city as a potent force in the cultural sector of India.

Legacy Institutions

Institutional spaces, such as the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC), a multi-disciplinary space that holds installations, exhibitions, and performances, function as “traditional” settings, in which audiences can attend a show or production. Despite its more conventional aspects, the NMACC has helped launch significant transformations in Mumbai’s art scene. A private institution, the cultural centre aims to celebrate Indian culture and art, and has further provided the city a space where events or exhibitions are organised for the sole intent of viewership, consumption, or participation, like many of the events Rajan has led there. The NMACC, operating as a gallery and a theatre, has allowed spectators a new level of accessibility to arts and culture, offering a selection of programmes and public installations. With limited support from the government, individuals are tasked with constructing platforms for both artists and consumers.

The Grand Theatre, NMACC. Image courtesy of NMACC.

TOILETPAPER: RUN AS SLOW AS YOU CAN, curated by Mafalda Millies and Roya Sachs of TRIADIC, NMACC. Image courtesy of NMACC

Community Spaces

Social spaces, instead, maintain the gallery aspects of the former, but encourage active engagement from visitors. Transforming the space beyond just a site of spectatorship, these galleries, such as Chemould Prescott Road, Experimenter, Nature Morte, Method, and Jhaveri Contemporary, are actively working on curating intricate spaces, experiences, and opportunities. Chemould, one of the city’s oldest and most established art galleries, for example, launched Chemould CoLab, an initiative that supports young, emerging artists. Method also held the performance “Continuum” by Akanksha Akkudev in September of 2023, in which the artwork moved according to the artist’s dancing and breathwork. All of these galleries also participate in Art Night Thursday, closing later than regular timings and sometimes offering previews of new exhibitions. Further pushing the boundaries between physicality, participation, and art are multidisciplinary-spaces like the G5A Foundation, an organisation based out of a refurbished warehouse in the Girangaon area, has a variety of initiatives that focus on nurturing creativity. Through their multiple spaces, known collectively as “the Warehouse,” G5A hosts performances,

conversations, and poetry readings, and even houses a restaurant. The foundation’s projects extend past this physical warehouse. The Forum is a series of artist residence spaces, and their project CityLab aims to preserve and revitalise the surrounding neighbourhood, working alongside the local community to organise workshops and walks, in turn creating a sense of placemaking. With a focus on supporting an arts education, they also have the Academy, which offers workshops and courses taught by artists for other artists, and Imprint, an arts and culture magazine, entirely digital.

LOJAL Performance at the Warehouse, G5A Foundation. Image courtesy of the G5A Foundation.

G5A Foundation. Image courtesy of the G5A Foundation.

The Black Box at the G5A Foundation. Image courtesy of the G5A Foundation.

Other places innovatively infusing art, design, and experiences include restaurants like Neuma and Noon, for example. Designed by Ashiesh Shah, a renowned architect from the city, the spaces celebrate Indian art and craftsmanship, intricate details that further accentuate the country’s vibrancy without necessarily boxing them into a formal gallery or museum setting. With efforts like these, art in Mumbai is not only becoming increasingly experiential and participatory, but invested in fostering involvement from younger audiences.

Grassroots Initiatives

Experiences are significantly more valuable. “It is one thing to exist in a space and another thing to be primed to experience that space,” Rajan asserts. Spaces are becoming increasingly aware of how to create a meaningful way of connecting with the audience, and focusing on how something feels, rather than how it looks. With the constant introduction of technological advancements, the act of seeing a venue or show itself has become obsolete; “sight” is no longer a truly human feature, and we can see visuals through a screen. Yet, aspects like scents and textures cannot be replicated, making a multi sensorial experience truly enriching. Therefore, every space has to have something that happens intentionally at a spiritual, emotional, and mental level.

Places like IF.BE, a multidisciplinary cultural space, are also reinventing both the physical and the experiential. Once an old ice factory, IF.BE’s original structure remains largely unmodified, but the space now serves as a location where the arts, community, architecture, and dining intersect. The venue recently held the Youth Collectors Weekend, in which they promoted local, contemporary artists and their works to new and young collectors, as an effort to make art more accessible.

They have since expanded on the ice factory, as well, with adjacent structures such as “the Cathedral,” their approach on a contemporary shrine, “the Substation,” serving as a gateway to the rest of the building, and a courtyard and café. Across the various spaces, IF.BE often hosts poetry readings, film screenings, workshops, and lectures.

How Are You Feeling? Studio, a creative duo that organises exhibitions and performances across the city, had their piece “Provenance,” a monolith of red-ice, originally set at IF.BE as a nod to the space’s history. As the ice melted and the installation disappeared, the piece both historicized the space’s context and gave it new meaning. Other places include the Great Eastern Home, a former cotton mill that now operates as a furniture store, but occasionally holds events such as music festivals and performances, and Snowball Studios, a production studio that also does immersive experiences and exhibitions.

“I find it fascinating to study the lack of physical space –– specifically free, public, open spaces –– and how this influences how people occupy the city,”

Whereas some places are hyper aware of their physicality, and the importance of their presence, other spaces often play with temporality. Space118, in contrast, has no physical presence, operating entirely online. Once a warehouse dedicated for artist studios and residences, the pandemic forced the space to reimagine how to continue supporting and highlighting art. It has since transformed into a digital space, which offers artist residencies, workshops, and lectures online. Serving almost as an “anti-gallery,” Space118 is further extending the frontiers of how we consume and participate in art.

Public spaces like St+art India Foundation and TheStepsBandra, and even places typically removed from the arts scene, such as the Bandra Kurla Complex, the Sea Link, and the India itself have become cultural spots or hubs, challenging what we think form official spaces and artistry. St+Art India works entirely with urban art. Through murals and graffiti in a variety of places like public buildings, the Ukkadam Art District, and schools, the foundation is using the transformative power of the arts to foster change. TheStepsBandra is a multi-use public art space that offers public dance performances and live music. Designed by BombayGreenway, an architecture platform that aims to map out and transform the city, the space and its events are entirely free. The BKC houses the NMACC, while the Sea Link has started projecting animations at night. Dior’s Autumn 2023 show took place in the Gateway of India, further highlighting Mumbai’s richness and craftsmanship and positioning the city as a potent force. These “open air” galleries completely transform who has access to art.

In Mumbai, the entire arts ecosystem is symbiotic: to operate, interact, and flourish, collaboration is essential, and places are challenging what it means to be a viewer, to present an exhibition, and to exist in a space. Mumbai’s ever-changing, fast-paced environment is breeding collaboration, and forcing industries to work together, support each other, and uplift their communities. With the need to maximise a place and a new generation emerging, facilitators are increasingly more responsible for making the arts community-based, important, and approachable. As art becomes a more viable profession, and people become more exposed to multi and interdisciplinary approaches, Mumbai’s cultural landscape continues to grow and change. Issues of accessibility still remain, but “where India is headed is found in Mumbai.”