Aimee Dawson

When one thinks of Egypt, it evokes images of mighty pharaohs, walls of hieroglyphics and, of course, the iconic pyramids. Ancient Egypt is one of the most enduring civilisations in contemporary culture and its popularity brings hoards of tourists to the country every year. While millions of dollars are invested by the Egyptian government into projects around its history — the long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum, located close to the Pyramids of Giza, is reported to have cost more than $1 billion — there is very little state investment in other forms of culture. For this reason, the country’s contemporary art scene is made up of mostly independent, citizen-led projects and spaces.

Cairo has a significant history as an important site of Islamic art and architecture, as can be seen in the state-run Cairo Museum of Islamic Art and in the city’s old neighbourhoods where the styles of bygone empires—including Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman—can still be seen on the facades of the buildings. Many of these crumbling streets are being preserved and brought back to life by locals and private organisations. Egypt underwent great political struggles during British colonial rule (1882-1922) but it also brought with it the Al-Nahda movement, or “Arab Awakening”, which saw cultural reforms influenced by Western ideals. Cairo became a hub for artists and intellectuals. The first School of Fine Arts in Egypt was founded in 1908 and the city was abuzz with cultural salons and arts collectives.

Nearly a century later, in 2011, the Arab Spring swept through Egypt and saw millions of people take part in anti-government protests, leading to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak. For weeks, thousands of demonstrators occupied Tahrir Square, a central position in Downtown Cairo, and filled it with creativity, such as DIY film screenings, poetry readings, and graffiti art. Many more grassroots initiatives have sprung up since. This, as well as the increased time spent online during Covid lockdowns, broke down many barriers for Egyptian artists, bringing an emergence of self–taught artists in Egypt.

Here, the Cairo-based visual artist and interior architect Karim El Hayawan, shares some of his favourite art spaces in the city whose cultural and historical significance has led it to be known in Arabic as Umm Al-Dunya or “Mother of the World”.

“Egypt is a huge patchwork of people, communities and histories,” says El Hayawan. “Often, however, Ancient Egypt overshadows so many contexts and situations. It’s so intricately woven into life. It’s not just in museums: people live all around the pyramids, for example. Ancient Egypt is part of us.” That being said, Cairo also boasts important sites from more recent civilisations. Exquisite examples of Islamic art and architecture can be found in the state-run Cairo Museum of Islamic Art as well as in the city’s old neighbourhoods where the styles of bygone empires—including Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman—can still be seen on the facades of the buildings. Old Cairo, which is a UNESCO Heritage Site, is an important part of Egypt’s “patchwork” that El Hayawan mentions. “It is full of old architecture and designs that are so organic and chaotic. It has a special charm,” he says. He created a project called Between Here & Elsewhere, inspired by the historic mosques in the neighbourhood. “One day I realised that the floors were covered in a literal patchwork of rugs, which are donated by the people who live nearby. The mosque keeper lays them all out and becomes like a collage artist or curator in his own right. I began documenting these rugs and recently I collected some of them and recreated the mis-match floor at the Cairo Citadel.”

Recognising the area’s historic importance, many of the crumbling streets in Old Cairo are being preserved and brought back to life by locals and private organisations. Bayt Yakan is a historical house that represents one of Egypt’s best restoration and preservation projects, El Hayawan says. The 17th-century building was bought by husband and wife Alaa el-Habashi and Ola Said in 2009 to save it from demolition.

Since renovating the house it is now open to the public, hosting craft workshops and selling local products. Alaa also has an impressive library that he opens once a week for the public to enjoy. There are also five or six rooms for artists residencies and studios, and the space is available to hire for photoshoots and events, which generate some income to maintain the place. Ola and Alaa also host weddings and engagement parties for free for people in the neighbourhood. “While so many people have moved out to the suburbs as Cairo expands, Alaa decided to delve back into the old town and this project is encouraging others to buy the old houses and renovate them, too,” El Hayawan says. “He is trying to create a network of these buildings to turn it into an attraction for people to come and visit.”

The Library of Bayt Yakan. Image courtesy of Bayt Yakan.

Bayt Al-Suhaymi Project. Image courtesy of Nadim Foundation.

The Nadim Foundation also supports heritage. The non-profit, non-governmental organisation (NGO) aims to preserve heritage by documenting it. For example, the team has documented all the woodwork in Old Cairo, such as the doors and mashrabiya (latticework screens) and created an open source library for people to search all the photographs, called the Encyclopedia of Egyptian Woodwork. “While there’s a lot of documentation and preservation of Ancient Egyptian sites, there’s very little documentation of Old Cairo. It’s a big shame,” says El Hayawan. “This is key to preserving Cairo’s heritage for future generations.”

“Egypt is a huge patchwork of people, communities and histories,”

Another important NGO in the area is Megawra, a hub for young students and architects to come together that is also open to the public. It focuses on the fields of architecture and urbanism through art and cultural heritage and emphasises their role in promoting sustainability and social responsibility in the city. The organisation hosts all kinds of events, from workshops on graffiti to treasure hunts for children. “They’ve been doing a great job and have really become part of the community there, which is important if you want to make a difference,” El Hayawan notes.

The past five to ten years has seen a lot of changes in Cairo, and in Egypt more widely, El Hayawan says. In 2011, the Arab Spring swept through Egypt and saw millions of people take part in anti-government protests, leading to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak. For weeks, thousands of demonstrators occupied Tahrir Square, a central position in Downtown Cairo, and filled it with creativity, such as DIY film screenings, poetry readings, and graffiti art. Many more grassroots initiatives have sprung up since. This, as well as the increased time spent online during Covid lockdowns, broke down many barriers for Egyptian artists, bringing an emergence of self–taught artists in Egypt. “The younger generation are less interested in the past and are more keen on living their day to day lives and expressing those experiences,” El Hayawan says. “The gap between the older generations and the young generation of artists is huge, from their exposure to the world and their ambitions, to their subject matters and means of expression.”

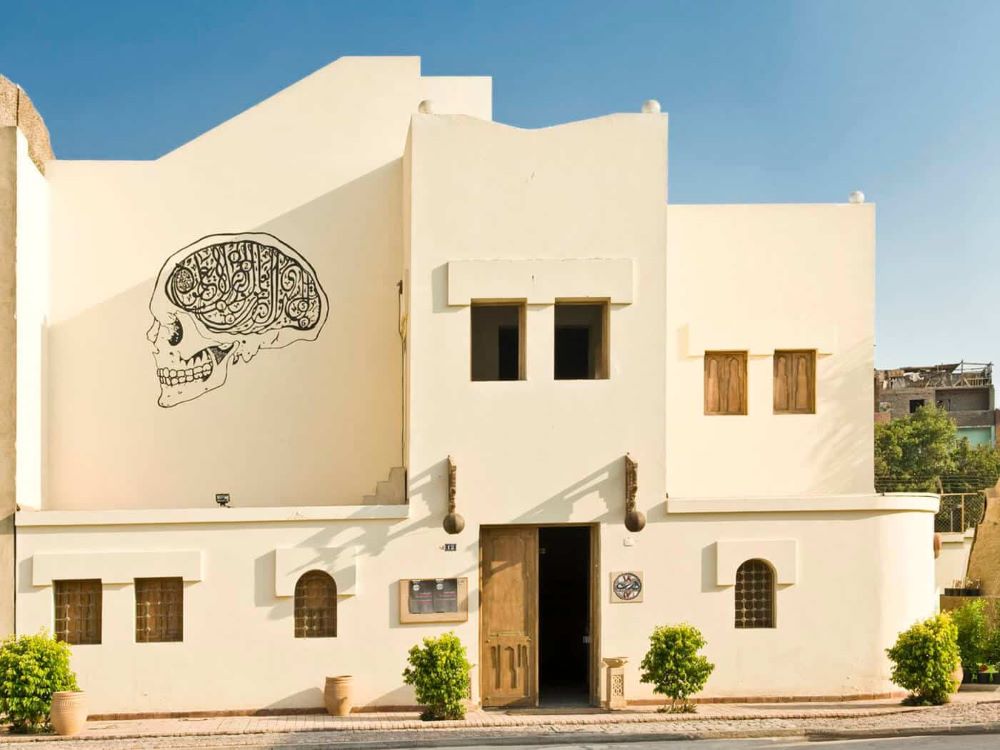

Opportunities for young artists are few and far between in Cairo. “I personally owe a lot to Darb 1718” says El Hayawan. The contemporary art and culture centre located in the Fustat area of Old Cairo was the first space he ever exhibited, around 15 years ago. “The founder-artist Moataz Nasr reached out and told me that he loved my work.

Darb 1718 in Futsat, Old Cairo. Image courtesy of Darb 1718

That exhibition led to so many more opportunities for me internationally and I’m sure Moataz has done the same for hundreds of other artists,” he adds. Darb 1718 hosts workshops and artist residencies as well as music and film events. In 2023, the government suddenly decided to demolish Darb 1718’s buildings to make way for a new road. Despite protests, the main building was destroyed in January. The organisation is continuing to work in some of the smaller spaces that remain. “Darb 1718 stands for more than just a building,” argues El Hayawan. “You cannot demolish an idea or a community. If we need to, we will rebuild it somewhere else.”

Medrar for Contemporary Art is another important space for the younger generation of artists. The art centre is open to all genres and mediums of art. It hosts competitions and exhibitions, runs the Cairo Video Festival and produces Medrar.TV, a web-based video channel that documents Egypt’s independent art scene. “It is a very progressive and inclusive initiative that allows artists to experiment,” El Hayawan says. “It’s a very liberal space, and I would say it’s also a very liberating space. It’s an important place to go to find out about what’s happening in the contemporary art scene.”

‘Roznama’, a periodical competition and exhibition for contemporary visual art by young Egyptians, at Medrar for Contemporary Art. Images courtesy of Medrar.

A particular passion project of El Hayawan’s is Tawasol, an NGO that supports communities in three of Cairo’s informal slum areas: Ezzbet Khairallah, Istabl Antar, and Batn el Ba’ara/Dar Al Salam. It is the brainchild of Yasmina Abou Youssef, who in 2008 began helping underprivileged children with craft workshops. She soon realised that it wasn’t sustainable so she raised some funds, bought an old building in the area, and turned it into a community school, where the children are now taught academic classes, performing arts and craft-making. Tawasol sells the products made in class and 100% of the proceeds go back to either the students as wages or help towards sustaining community development projects. “This initiative is very practical and pragmatic, as many of the parents wouldn’t let their children go to school because they needed them to bring in money for their family,” explain El Hayawan. “In 2020, Yasmina was able to expand the project and built a new community school that accommodates 500 children, which I helped to co-design with Nehal Leheta, and our studio, Design Point. It has a huge boutique for the products the children make, but they are also sold all over Cairo.” Tawasol is also well known for its theatre productions, including a massive play every Ramadan, and the shows often travel to other bigger venues in Cairo. Three generations have graduated from the theatre school there now. “The parents are really proud of their children, and the children take a lot of pride in their work and their education,” El Hayawan says. “Everyone in the area is so engaged. I give a lot of workshops there and we also held a huge exhibition in 2023 in Downtown Cairo. Everyone celebrated their work and now they all want to be artists!”

El Hayawan argues that the Egyptian government is more invested in “national projects” that mostly relate to ancient culture than in contemporary art and culture. “In a way this has been a blessing,” El Hayawan reflects. “It gives a lot of room for civil society to work and create grassroots projects. It’s better that these organisations are unbiased, organic, and owned by no one, in my opinion, but perhaps I’m an optimist.” He points out that in recent years many new art and culture projects have launched in Cairo and beyond, such as Cairo Design Week, Art d’Egypte, El Gouna Film Festival and Cairo Photo Week. “Now the art community has become a force and the government is beginning to follow our lead and it is opening up public space for us. The state has finally realised that if they build this bridge then the exchange of communication could be interesting and valuable to them, culturally and economically,” El Hayawan says. “Of course, there are still challenges. But this dialogue between civil society and the government is necessary. Trust is slowly being built and Egypt’s public spaces are being revived.”